Atlantic Classical Orchestra Presents

The Best of Beethoven, Vladimir Feltsman, Piano

First in our 2013 Series

Vladimir Feltsman, Piano

PROGRAM

Coriolanus Overture

Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, Op. 73 ‘Emperor’

Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21

One great composer, three powerhouse works. Conductor Stewart Robertson and the Atlantic Classical Orchestra present an all-Beethoven concert drawing attention to the composer’s sheer brilliance in capturing human spirit and emotion.

Inspired by a play (not Shakespeare), about the dilemma of a heroic political leader torn among the conflicting forces of patriotic impulse, family devotion, and personal pride, Beethoven’s dramatic Overture to Coriolanus is excellently paired with the contrastingly vibrant and playful Symphony No. 1. A piece praised by his contemporaries as a “masterpiece”, the First Symphony was (and still is), considered “just as beautiful and distinguished in its design as its execution.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Pianist Vladimir Feltsman is one of the most versatile and constantly interesting musicians of our time. A regular guest soloist with leading symphony orchestras in the United States and abroad, he appears in the most prestigious concert series and music festivals all over the world. In all his virtuosic flair, Feltsman punctuates the program with excitement of the grand ‘Emperor’ Piano Concerto. Excerpts of previous Vladimir Feltsman performances can be heard at www.feltsman.com

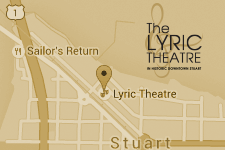

To purchase your 2013 Atlantic Classical Orchestra Season Subscription please call the Lyric Theatre Box Office at 772.286.7827.

Program Notes

Ludwig van Beethoven Coriolan (Coriolanus) Overture, Op. 62

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn in 1770 and died in Vienna in 1827. He composed his Coriolanus Overture in 1807 and led the first performance in Vienna the same year. The Overture is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

Beethoven had read Plutarch’s Lives, and he was familiar with Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, but it was the Austrian playwright Heinrich von Collin’s tragedy of the same name that inspired him to compose this piece. He also badly needed a new concert overture, for he had been using The Creatures of Prometheus over and over and it was past time for something new.

Gaius Marcius Coriolanus was a brave and imperious Roman general who had led his army in triumph over the neighboring Volscians in 493 B.C. As a patrician Roman he had a bone-deep contempt for the masses, and was boorish enough to say so in public. In the senate he tried to abolish the office of Tribune of the Plebs—the underclass’ only representative in Roman government. This caused a near-riot in Rome, and Coriolanus was brought before the people’s assembly to be tried for attempting to overthrow the government. He was found guilty and sentenced to exile. Furious, Coriolanus hired himself out to the very Volscians he had defeated and marched on Rome with their armies. When he laid siege to the city, Rome’s frantic leaders sent emissaries to Coriolanus to persuade him to withdraw, but nothing would change his mind. Finally a group of women, including Coriolanus’ wife and mother, came to plead with him and Coriolanus finally relented. Accounts vary as to what happened next; at this point in the story Shakespeare had him killed by the Volscians for his treachery, while in Collin’s play he committed suicide—an act considered by Romans to be the proper response to dishonor.

Beethoven’s Overture is not programmatic in the way we might expect a work from Berlioz or Wagner to be: he makes no attempt to tell the whole story. But his sonata-allegro form is a perfect medium to express Coriolanus’ torment as he is forced to choose between revenge and mercy. After the stentorian opening chords the first theme we hear is clearly Coriolanus himself, stubborn and imperious. The second, gentler theme is the entreaty of his wife and mother. In the development these themes confront each other as they must have in Coriolanus’ tortured mind. Finally, those opening chords return and we hear the music ebb away, along with Coriolanus’ life.

Ludwig van Beethoven, Concerto for Piano & Orchestra No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73, “Emperor”

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn in 1770 and died in Vienna in 1827. He composed this work in 1809, and it was first performed in 1811 by Friedrich Schneider with the Gewandhaus Orchestra Leipzig, Johann Schulz conducting. The name “Emperor” didn’t come from Beethoven; there are conflicting theories about how the concerto acquired it. The work is scored for solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani and strings.

Had Beethoven known that one day his Fifth Piano Concerto would be known as the “Emperor,” he would not have been amused. In 1809, while Beethoven was composing the work, Vienna was being attacked and later occupied by Napoleon’s troops. At one point Beethoven had to take refuge in his brother’s basement: “The whole course of events has affected me body and soul. What a disturbing, wild life around me! Nothing but drums, cannon, men, misery of all sorts!”

Years previously, Beethoven had felt an affinity between himself and Napoleon, a self-made man of professed republican intentions; he even wrote his Third Symphony with Napoleon in mind. But when the Frenchman proclaimed himself emperor and set a course for world domination, Beethoven reacted bitterly: “Now he, too, will trample on all the rights of Man and indulge only his ambition. He will exalt himself above all others, become a tyrant!” Beethoven so violently scratched out Napoleon’s name on the symphony’s dedication page that he went right through the paper. Under the circumstances, “Emperor” was the last title Beethoven might have chosen for a work composed while under attack.

Beethoven never wrote an ordinary concerto: there’s something unusual around every corner. While most concertos lay out the themes in the orchestra before the soloist enters, here the piano launches right in, only to fall silent. This deceit creates a certain tension about when it will re-enter. Later, at the place where we expect to hear a cadenza, Beethoven specifically forbids one, instructing the soloist to push on.

The theme-and-variations second movement begins in the unexpected key of B-major, about as far removed from E-flat as can be. Its ending is pure genius. The piano ruminates, inventing a new melody note-by-note; it keeps adding notes until it achieves the opening theme of the Finale, which follows without pause.

This Rondo is an astonishing dissertation on the use of form. The first episode of the rondo is in fact a sonata form; the second episode is itself a miniature rondo. You might only hear these forms-within-forms and compositional devices if you deliberately listen for them, but they create a finely crafted, multi-layered cohesiveness—and music that sounds utterly fresh and spontaneous.

This remarkable concerto was Beethoven’s last, even though he would live a further eighteen years. The piano concertos had been vehicles for his own prodigious pianism, but by this time he had grown too deaf to perform. Despite the cruel irony of his affliction and the frightening scenes around him, Beethoven left us a magnificent work of noble spirit and profound affirmation.

Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn in 1770 and died in Vienna in 1827. He completed his First Symphony in 1800, and conducted the first performance in Vienna the same year. The symphony is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

It’s often said that you can hear Beethoven’s debt to Mozart and Haydn in his First Symphony, and that’s true as far as it goes. Haydn had been Beethoven’s teacher for about a year, but their relationship was stormy. Beethoven resisted Haydn’s teaching of the “rules” of composition, for the old master himself was known for honoring them in the breech as much as in the observance. Like most young men, Beethoven wanted to break the rules as well, and was impatient about it. And he was probably self-assured enough to realize that in his hands the symphony would be wrenched summarily from the 18th century into the 19th.

Beethoven set about breaking the rules from the first notes of the First Symphony to the last. The third movement Minuet is a perfect example. The minuet was a courtly dance in a medium-tempo three-beats-to-the-bar meter. But Beethoven’s Minuet trades the stately elegance we expect for a jocular, much faster, one-to-the-bar movement more perfectly described as a scherzo. (The word scherzo implies humor, not speed, but most scherzos are fast.) In this, Beethoven himself established the “rule” that subsequent symphonists would follow: after his First Symphony no one wrote minuets anymore.

At the remove of 200 years it is easy to take this kind of innovation for granted, but all the broken rules were quite a shock to some of Beethoven’s contemporaries. A reviewer of the first performance of the symphony complained it was “the confused explosions and the outrageous effrontery of a young man.” Another critic called it “a danger to musical art. It is believed that a prodigal use of the most barbarous dissonances and a noisy use of all the instruments will make an effect. Alas, the ear is only stabbed; there is no appeal to the heart.” Ludicrous notions, of course; these men might have fainted had they heard the music of Wagner. So while we can smile at the quaint moments in this symphony that remind us of Haydn, it’s worth remembering that Beethoven was, in his time, the avant garde. What he began with the First would continue beyond anyone’s ability to imagine through the rest of his nine, and the symphony would be changed forever.